Corporate impunity and seed sovereignty: Interview with the Rural Womens’ Assembly (RWA)

Interview conducted by Defending Peasants’ Rights in October 2025, on the occasion of the 11th session of negotiations for a UN legally binding treaty to regulate transnational corporations, held at the Human Rights Council in Geneva.

Interviewees: Lungisa Huna – RWA South Africa; Grace Tepula and Precious Shonga – RWA Zambia; Zakithi Sibandze – RWA Swaziland.

1: What is the Rural Women’s Assembly and what are your key areas of work?

The Rural Women Assembly is a network of movements of peasants, fisher folks, farm workers, migrant and landless women, all living and working in the rural areas in the Southern Africa region. We are in 11 countries, with a membership of close to 200,000 members. So it’s a very unique movement of rural women in the region.

Essentially, the Rural Women Assembly builds the voice of rural women and builds agency in relation to questions of access to land and water; the right to food; the right to seeds; and of course, we deal with patriarchal issues that affect women particularly in rural areas. Also central to our work is the issue of climate justice, which has a substantial impact on the region, largely due to the many cyclones that strike it repeatedly, as well as other climate-related crises.

Furthermore, we deal with cases of gender-based violence. In this regard, we develop study cycles in different countries, which are spaces that allow us to discuss on issues related to violence against women.

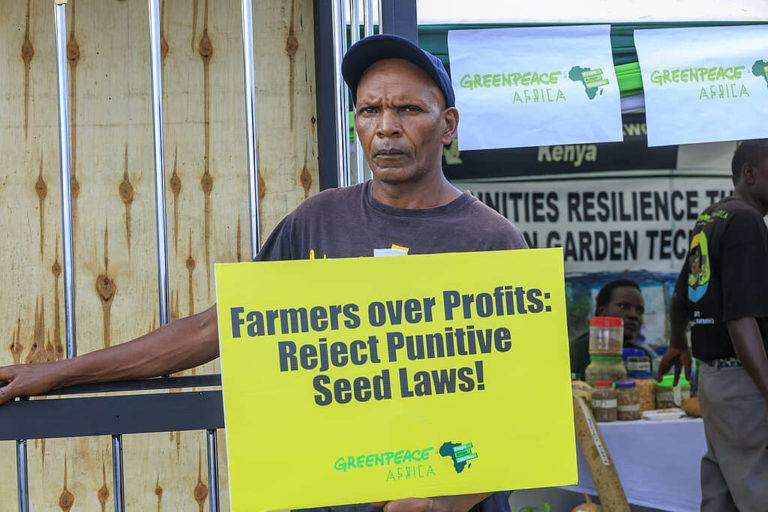

We are also the guardians of our seeds, because we believe that seeds are our lives, our heritage, our identity, which we don’t want to lose. We have a situation where the transnational corporations, the seed companies, want us to do away with our seeds, which we have inherited for generations and generations – and we’re resisting against that.

2: Why are you here in Geneva this week? What are your expectations?

We are here in Geneva for the 11th session of negotiation on a legally binding treaty to regulate transnational corporations (TNCs). We are here because our communities are experiencing violence from transnational corporations every day. The people in the communities are being grabbed off their land, where we do farming as women. We also have issues of climate crisis, as already said. These companies should pay for the pollution, the damages and the losses that we’re experiencing each and every year. It’s drought, it’s floods… So that is why we are here, so that we can contribute to the elaboration of a binding treaty to hold these companies accountable. Our goal is for the treaty to be out so that we are able to prevent these catastrophes.

We are here to have our voices heard, because when we’re in our countries we can issue statements, but they don’t reach the United Nations. So we are here in multiple movements and communities, and a collective voice from different countries can carry weight.

We are here as part of the Global Campaign to Reclaim Peoples’ Sovereignty, Dismantle Corporate Power and Stop Impunity – a powerful coalition of social movements, progressive organisations and communities affected by transnational corporations – to raise the issues of the rural women in the Global South. Being here is critical for us and it’s part of our advocacy strategy as Rural Women’s Assembly. We want to invest and participate in different platforms to advocate locally, nationally, and internationally, and use these global policy-making spaces or even UN instruments to really amplify our voice.

3: How does the struggle for a strong binding treaty to regulate transnational corporations relate to the protection and implementation of peasants’ rights as outlined in the UNDROP declaration?

There is a strong connection. I was very pleased to hear about the inclusion, in Article 15.7 of the draft text of the binding treaty, of a provision on the rights of peasants and rural peoples, which received strong support from almost all countries, particularly from Colombia and Palestine. It speaks to the UNDROP that the rights of the peasants are included in this treaty. This instrument will help us to push forward the agenda of ours, which is pushing for the implementation of UNDROP in our countries. Whilst our countries, for example, South Africa, signed the declaration in 2018, we still don’t have a policy that implements UNDROP. Having this binding treaty in place will strengthen our advocacy and work back home to ensure that we hold our governments to account to implement both instruments. So, these two legal frameworks are going to be key vehicles for us to utilize in our advocacy strategies.

It is necessary to note that the violations committed by transnational corporations directly affect the very rights granted to us by UNDROP. In particular, the right to seeds, the right to land, and the right to water. Once this treaty is adopted, we will have a binding instrument to which we can refer in order to defend ourselves.

4: How do TNCs activities impact your communities?

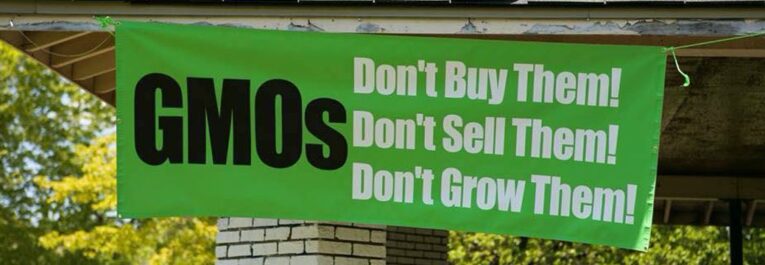

Firstly, TNCs want to take away our seeds and impose their own industrial seeds.. These enterprises pollute our water, causing a lot of diseases. The pollution affects not only people, but also animals and crops. As a result, we suffer from illnesses we don’t even recognise – sometimes even our own countries tell us they don’t know how to treat them. These are the impacts we are facing as a result of what TNCs are doing in our communities.

Seed sovereignty is no longer a right. Seeds have been commodified by transnational corporations. They have become a source of capital accumulation at the detriment of the rural poor. Our governments ignore that our seeds are resistant when it comes to the effects of climate change. Our seeds can be planted several times. When you buy hybrid seeds, they only last for a year. If you try to plant those seeds afterwards, they won’t germinate. Our seeds, on the other hand, are resistant – we can plant them for many years. Hence, we have food security at home and in the community. Our seeds are perfect. They are not harmful. They have healing properties and a lot of nutrients. You can cook the food coming from them in different ways. Sometimes they say there’s hunger in Zambia. It’s because they are following the corporate world’s thinking. If we could think like the rural women are thinking, there would be a lot of food in Zambia. There shouldn’t be even hunger in there. So, this treaty will also help us protect our seeds and our lives.

Hybrid seeds are expensive compared to our own kept seeds because they require fertilizers and chemicals. If you plant hybrids without any fertilizer, you get nothing. So, we are also trying to promote our own indigenous seeds, despite the threats we face from our governments. With the support of our governments, TNCs steal our seeds, make them hybrid, and make us pay the price for them. We have the right to say no to what they want to offer us.

Furthermore, they’re polluting the environment and they’re telling us we shouldn’t cut our trees so that the trees can clean up the carbon. They are interested in developing the carbon credit markets. They come into our areas, they grab big portions of land. They say, we shouldn’t even go and pick the mushrooms in there; we shouldn’t go pick the caterpillars in there. They put guards, so that we can’t go get the firewood. So, we have our own land, but we don’t have control of our own land. It’s very intimidating. They sell carbon with a lot of money, but we don’t get to get anything from there.

They grab land also because they want to do their mining, meanwhile we are displaced from a land where we’ve lived for so many years. They even damage the graves that are on the land. That is very de-humansing. There’s a lot of impunity in what they’re doing.

These TNCs have destroyed our land with pollution. You have a field that you cannot use for the next 10 years because it has been damaged with unknown toxic minerals that have passed through the area. In the Zambian Copperbelt province, which is near where we stay, TNCs polluted the Kafue River, which runs across the whole country. We can’t access the water in three quarters of the land through which the Kafue River passes. We can’t eat any fish from there.

In South Africa, fisher folks have taken up our government – particularly our Department of Mineral Resource and Energy – for blasting on the oceans, for working and collaborating with the Shell company, which was looking for oil in the ocean in the eastern part of South Africa. We have a similar case in terms of Titanium that has been going on for a long time also in the eastern part of South Africa, in Mbizana, where the communities are standing up and saying, ‘we have the right to say no’.The principle of free, prior and informed consent of the concerned communities should be respected. This has been a long process of litigation and these transnational corporations must be held accountable. They need to pay. We need reparations. Through the process of resisting, lives were lost, defenders have been killed and many are being threatened as we speak.

5: How have you been mobilising the UNDROP declaration in Southern Africa in favour of rural women’s rights?

Firstly, we made sure that our members understand what this declaration stands for and therefore what are the rights that are contained in it. We went through a strong move of capacitating, educating and building awareness amongst our members on their rights and how to engage to defend them. It is a declaration adopted by the United Nations that every country must implement, so it was critical for us to make sure our communities understood their rights. Each country has an advocacy strategy, they amplify the UNDROP in their communities. We have a booklet which is featured on our website, and we carry it everywhere. In every opportunity we have in engaging the duty bearers or government officials, we use this as a tool to engage and empower communities.

For example, in South Africa, we have been running a campaign called “One Woman, One Hectare of Land”, to provide more land for women. We combine that campaign with the UNDROP, especially the right to land, the right to food sovereignty, the right to use our seeds.

As rural women across different countries, we hold food and seed festivals every year. We do that to identify what seeds were lost, what we still have, how we can make better use of each seed. We now want to make seed banks and demo fields where we can be planting these seeds, so that we can multiply them. We also develop seed sharing initiatives. We work to increase our seed stocks so that, as we resist transnational corporations, we also show the strength of what we have.

In Swaziland, for instance, we are engaging government officials in the implementation of UNDROP. We have engaged with several ministries, including the Ministry of Agriculture, but concrete results are yet to come as they have not yet prioritised the issue. We also started with translating the UNDROP to the local languages so that it is accessible to our people, to the women.

6: What is your message for Southern African states regarding their engagement in the Binding Treaty process?

What is critical in this podium is to hear the voices of the Global South, especially our African governments. We want them to stop corporate impunity. The should take action for our people, for our communities, for the poor, for our nations. In South Africa, for example, we have a great human rights constitution. South Africa has signed declarations, and has been historically committed to the UNDROP. Therefore, we demand that our voices are heard and that these instruments are implemented.

We wish more African countries were actively engaging in this Binding Treaty negotiation process. The governments should step in, find markets for our indigenous foods and promote them, and help the peasants. If we don’t have maize, there’s sorghum, there’s different types of beans, there’s cassava. We can make a meal from that. So they should put the lives of their people first rather than protecting these so-called investors that are coming into our countries just to plunder. They extract the minerals, take them away, and when they return, we are forced to buy our own resources back at a very high price.

If corporations are coming as investors in our countries, let them build schools, roads, hospitals. The government should stand up and fight for us. Stop looking at the profits, and look at the lives of our people!