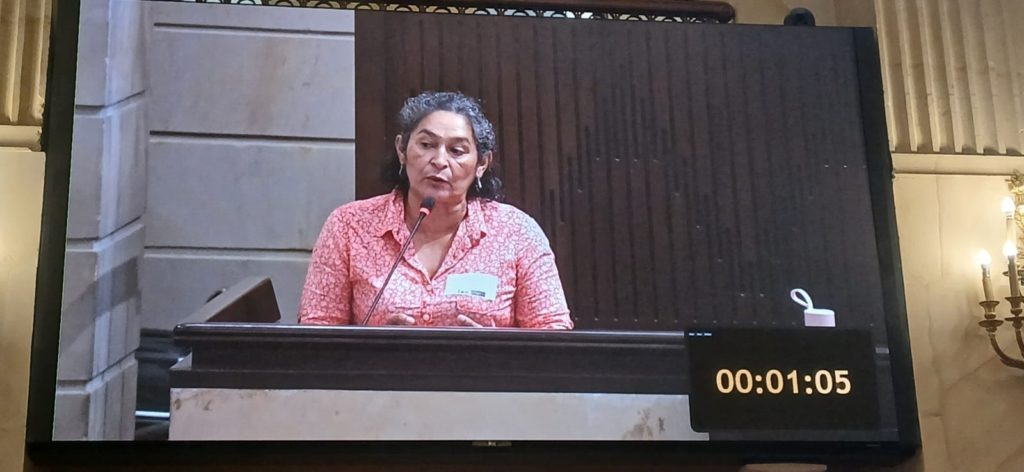

Colombia: Recognition of peasants in the Constitution – Interview with Martha Elena Huertas Moya

On July 5, 2023, Colombia reformed its Political Constitution, in particular Article 64. Since 1991, Article 64 has laid down the State’s duty to help agricultural workers gain access to land ownership, as well as to a series of rights enabling them to enjoy a better standard of living. This duty remains in the new version of the article, with the addition of recognition of the peasantry and peasants as subjects of specific rights. The article recognizes that they have a particular identity, linked to their relationship with the land and territory, and that this gives them a specific status as political subjects.

The peasantry is a subject of rights and special protection, has a particular relationship with the land based on food production as a guarantee of food sovereignty, its forms of peasant territoriality, geographical, demographic, organizational and cultural conditions that distinguish it from other social groups.

Article 64 §2, Constitution of Colombia

This recognition is the culmination of a long struggle on the part of peasants and their representative organizations. To fully understand the importance of this change in the Constitution, how it was obtained, the role of UNDROP in this new achievement and the next steps to be taken, we interviewed Martha Elena Huertas Moya from the peasant organization FENACOA.

Can you introduce yourself and your organization ?

Thank you, I am Martha Elena Huertas Moya, a peasant born in rural Bogotá, with permanent ties to my community. I have been a member of the National Federation of Agricultural Cooperatives, FENACOA, since its foundation 40 years ago, as an educator and in the last decade as a member of the Board of Administration.

FENACOA, a second level organization, groups cooperatives and associations of the social and community economy in some regions of the country, such as Guaviare, Meta, Cundinamarca, Tolima, Cauca and Caldas.

We are an organization still not recognized as a victim of socio-political (structural) violence and the social and armed conflict in Colombia. In the 90’s, 2 acting managers and other leaders from our member organizations were assassinated, another part of the leadership was imprisoned, leaders and associates were threatened and exiled.

We are also a member organization of CLOC LVC, from the beginning, and member of several platforms of struggle for the integral agrarian reform in Colombia.

The main objective as an agricultural cooperative sector, and particularly in the current situation of the Colombian government with its development plan “world power of life”, is to contribute to the economic reactivation of the country in the primary sector, to contribute to the agro-ecological and energy transitions and the social and political transformations necessary for the full exercise of the rights of the peasantry. In fact, the latter was recognized as a subject of special protection thanks to the global struggle led by the La Via Campesina.

Could you tell us about the situation of peasants’ rights in Colombia, particularly after the election of Gustavo Petro as President?

President Petro, and his government program represent for the Colombian peasantry the opportunity to

a) to be recognized in the national political constitution as political subjects of rights with special protection, in order to have access to the exercise of the rights contemplated in the UN Declaration on peasant rights.

b) to resume the implementation of the peace agreement, which contemplated among other things the implementation of the integral rural reform, through concrete goals such as the purchase of 3,000,000 hectares for adjudication, formalization, restitution and reparation to the peasantry.

c) to make the necessary social and political transformations required for the peasantry and rural workers to have a dignified life.

Have you seen any progress, in terms of agrarian reform for example?

The changes and progress observed since Gustavo Petro’s administration took office are clearly observable, not only in legal and constitutional measures (normative and regulatory frameworks, laws, decrees, resolutions, etc.), but also at the level of agrarian law reform proposals, which are obstructed and denied in the Congress of the Republic by the parliamentary majority, representative of latifundista interests. Despite these obstacles, important political actions are being implemented for the first time, such as massive land deliveries, financing of productive projects, recognition of peasant territorialities (peasant reserve zones, agri-food territories, among others). It should also be emphasized that these initiatives are taken through the prism of respect for the environment and the rights of nature, central elements required in the face of the current climate crises.

In addition, all peasants’ organizations have joined together to form the National Peasants’ Agenda. This group mobilized to put forward common objectives and proposals, which led to the signing of an agreement with the government. The agreement signed in July 2024 contemplates the implementation of agrarian reform, rural development, economic reactivation, productive projects, coca crop substitution and other issues.

These agreements signed on July 10, 2024, ratify the joint and articulated work between the government and the Colombian peasant movement in the implementation of the Agrarian Reform, rural development, economic reactivation, productive projects, substitution of coca crops and others.

The peasant organizations demand an “integral and popular agrarian reform”, what does it mean for you compared to the “classic” agrarian reform?

Agrarian reform is the broadest and most significant concept for the peasantry. It is about having access to land, to ownership of that land, in a country where the ownership and tenure of the land is held by large landowners, and by food producing associations under the scheme of agro-industry (monoculture, agro-toxics, etc.). Colombia is a country where the most effective (counter) agrarian reform was carried out by large landowners and drug traffickers through a strategy of expulsion of peasants from their lands, through dispossession and other practices of occupation of land and peasant territories, with the critical support of paramilitary gangs.

For the peasantry, agrarian reform is integral to the extent that it guarantees the material and immaterial conditions necessary for the development of their life projects, in accordance with their cultural and social characteristics. This objective is woven in the perspective of being able to produce, transform and commercialize food for self-consumption and food supply to the population as a whole.

The integral reform, therefore, refers to all these structural changes and transformations (economic model, agrarian production model, model of the welfare system of public policy) to return to the peasantry the autonomy and sovereignty to produce food from the postulates of organic, ecological agriculture. This also includes, of course, the management of their seeds and the production of all the necessary bio-inputs. In conclusion, the reform has to be comprehensive in the sense of being able to guarantee fundamental rights such as the right to life, education, health, social protection, etc., etc., etc.

Can you explain the importance of the inclusion of peasants as political subjects in the Constitution?

Article 64:

It is the duty of the State to promote progressive access to land ownership for peasants and agrarian workers, individually or in association.

The peasantry is a subject of rights and special protection, has a particular relationship with the land based on food production as a guarantee of food sovereignty, its forms of peasant territoriality, geographical, demographic, organizational and cultural conditions that distinguish it from other social groups.

The State recognizes the economic, social, cultural, political and environmental dimensions of the peasantry, as well as those that are recognized and will ensure the protection, respect and guarantee of their individual and collective rights, with the aim of achieving material equality from a gender, age and territorial approach, access to goods and rights such as quality education with relevance, housing, health, public utilities, tertiary roads, land, territory, a healthy environment, access to and exchange of seeds, natural resources and biological diversity, water, enhanced participation, digital connectivity: improvement of rural infrastructure, agricultural and business extension, technical and technological assistance to generate added value and means of marketing their products.

Peasants are free and equal to all other populations and have the right to be free from any kind of discrimination in the exercise of their rights, particularly those based on their economic, social, cultural and political situation.“

In 1991, Colombia’s political charter brought significant changes to guarantee its essence as a social state based on the rule of law (the main achievement for decades was to overcome the state of siege and achieve a democratic opening). From then on, the main democratic freedoms were finally possible, beginning a long process towards social justice in a country with the highest rates of social inequality, the highest concentration of land ownership, and alarming indicators of humanitarian crisis.

The 1991 Constitution recognized the native peoples and Afro-descendant, Roma and Palenquero peoples, and recognized the rights of ethnic minorities. However, the peasantry was unfortunately excluded. In the territories, this lack of recognition had a serious impact on the exercise of the cultural, social, economic and political rights of the peasantry, especially as a subordinate sector, exploited and marginalized by structural classism and racism. Being recognized also as subjects of special protection, positioned us in parity to be another minority with rights, and these adjustments are the ones that are being harmonized within public policy.

What were the keys to achieving this change and, more generally, to implementing peasants’ rights?

For FENACOA, the achievement of this recognition is due to several factors:

1) the incorporation of the unfulfilled agreements of the Havana agreement in the public agenda of the State (beyond the government);

2) being an active part of the social movement of the government of Change.

3) having maintained a position as the largest social sector with outstanding political debt, as well as being considered the main victim of the violence of the social and armed conflict, and also of socio-political violence.

4) to have made an impact in public, social and community spaces with the Declaration of peasants’ rights, and to have this necessary pending as part of the integral agrarian reform.

5) to have an accumulation of struggles for integral agrarian reform.

Now that you have had this change, what do you think are the next major steps to implement UNDROP at the national level?

Colombia’s political right wing has installed magistrates, congressmen and officials who, for decades, have prevented, and continue to prevent, changes in favor of the Colombian peasantry. At this juncture, these high officials are at the forefront of blocking significant advances in agrarian policy.

We have difficulties at the level of the high courts (judicial branch), and the Constitutional Court in particular, which is reviewing the articles on peasant rights, in an open and clear challenge against Petro’s government (executive branch) and under the mandate of the latifundista right-wingers who are part of Congress (legislative branch). The objective is to close the way to the full exercise of recognized rights. In the face of this, we have to make permanent social, communicative and political mobilization to prevent the reversal of these rights and to ensure that progress is made on the agenda of the Declaration.

A second scenario is the Supreme Court of Justice, where the large landowner representatives demand the revision of the agrarian jurisdiction by this court, so that there will be agrarian judges to settle conflicts directly. This again is a move by the latifundista right wing to prevent the peasants from directly resolving the various conflicts they may have over land, titles, easements, water disputes, boundary disputes, among others.

Some organizations of CLOC-LVC Colombia launched a broad social mobilization, as members of the National Peasant Agenda, within which an agreement was signed to advance in the implementation and execution of peasant rights.

The full enjoyment of the rights of peasants and rural workers requires structural changes, and this will continue to be the struggle of the peasantry and other social and popular organizations. We recall that neoliberal capitalism is delaying every day any democratic and social attempt in Latin America.

And what are the main challenges ahead for the promotion of peasant rights and food sovereignty?

On the part of the national government, in the short term, the main challenges are:

- First, implement a mixed commission, as a permanent consultation mechanism between the State and the Colombian peasantry, necessary to harmonize public policies and governmental administrative structures in order to attend to the implementation of the integral rural reform.

- Secondarily, execute the government program that addresses the needs, demands and expectations of the peasant sector, this goes through fulfilling the agreements, minutes, etc. of previous governments.

Medium term:

- To set in motion the entire inter-institutional system to attend to the transformations required by the implementation of the integral rural reform.

- Create the conditions to shield the current advances from other governments that may try to undermine all these changes and transformations.

It is also necessary to highlight the challenges facing the peasant movement. In particular, the necessary consolidation and dialogue between the different peasant organizations, and also at the level of management and execution of productive projects, transformation, commercialization, etc. of the peasant, social, solidarity and community economy.

This challenge of consolidation also involves strategies and alliance relations with other sectors, with social, community and consumer processes, ensuring a permanent articulation with all social sectors of the country, in order to contribute to the strengthening of the social base that contributes to the political changes and transformations required by the country.